|

Voyage to Papua New Guinea

December 2002

| Nov 30 |

depart Honiara |

| Dec 12 |

arrive Alotau |

A beautiful voyage with a great deal of drifting in the right direction. We sailed when we could and motored when we absolutely had to. There were dolphins that came night after night to frolic on the bow, then upon arrival into Milne Bay the same group of spinners and bottlenose stayed with us on and off for 30 miles - Michel spent most of the last day hanging off the bolster chains! Creativity levels soared at sea with an Arabian Night in the library, a music jam initiating a new on-board band and a very heated evening sparked by a text from Krishnamurti!

But the best of all was our stop on a reef in the middle of the ocean ñ the reef has no name really, there is just a small sand cay on it. Itís close to an island called East Island. The reef is pretty much untouched by human hand and the fishlife showed this, both in the diversity present and in their behaviour. The reef rises very gently as a mount with a large reef flat at about 10m deep. Sharks were curious and plentiful (grey reef and whitetips), snappers came within inches of our faces, rainbow runners gathered in schools of forty or fifty, unicornfish enshrouded us on every dive, even the groupers didnít do their usual scarper into the nearest crevice in the reef. And the corals were pristine, really really perfect. Plus turtles, plus rays, plus more fish, more coral, more invertebrates. This spot is truly something else. Eddie, Michel and Stijn went fishing one night and caught 10 red snappers but when grey reef sharks started to bite, they decided to return to the ship. So we filled ourselves underwater, then filled the freezer before making the final stretch of miles to Alotau.

Alotau is still peaceful, the crew enjoy wandering the hills behind town in search of

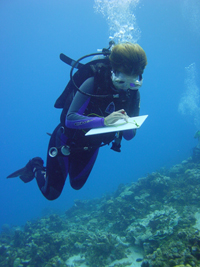

waterfalls and hanging out at the hotel bars while we get ourselves ready for the next leg of exploration. For dive training purposes, we bring the ship to the other side of the bay and explore the wreck. I am personally more interested in seeking sea horses but without luck.

| Dec 21 |

depart Alotau |

| Dec 22 |

arrive Magic Spot |

| Dec 26 |

depart Magic Spot |

| Dec 27 |

arrive Egum Atoll |

| Dec 30 |

depart Egum Atoll |

| Dec 31 |

arrive Kitava Island |

Gaie and Laser arrive for Christmas having stopped in Bali on their way to us. News exchanges take several days ñ there is so much happening so fast! We immediately whisk ourselves off to the depths of Milne Bay to show Gaie and Laser some of the incredible dive sites we found during our time here in August.

Sullivanís Patch is our first underwater port of call. Highlights here include a circling school of massive big-eye trevallies, gorgonians galer, very beautiful scenes but most beautiful of all, the dolphins that passed right in front of our bow as we readied ourselves to descend.

At Magic Spot, which remains utterly magical despite a slight reduction in visibility. On our first dive we encounter a giant grouper, somewhere in between the size of Gaie and Laser. The dive becomes tranquil and frenetic at the same time as we make our way along the wall, creeping shallower and shallower with each breath. The jacks get crazy, every species in the book. Sweetlips, unicornfish, the full complement of dancing characters. At Banana Bommie, we play with the darting anthias in a very strong current, holding onto the reef to watch them in their fairground displays behind

the branching tubastreas and massive coral heads. Itís a hilarious show.

The continual diving breaks up the endless meetings which take place on board, discussions and preparations and organisations for the looming Pacific crossing. There are so many aspects to cover, so many lists to write and so many scenarios to anticipate.

And the multi-cultural Christmas celebrations include a German feast on the 24th prepared by Ferdi and Linda (followed by the new Bond movie, sent to us from

Yves to complete the festivities!) and a six course gourmet celebration on the 25th from a team led by Michel. Christmas Day sunset is one of

the most incredible we have seen in months.

As we move the ship overnight to Egum, there is a flicker of activity around our new fishing gear, a fancy reel and a lucky lure ñ a fish bites but escapes before we can haul it in. A good omen though for our fishing future. Egum Atoll is an action-packed stop for us. In total we are anchored inside the atoll, next to the island of Yanaba, for just three days in the course of which we dive relentlessly on the atoll entrance, perform dances from Simbo and Mbambanga in exchange for their Trobriand-style dances, scrutinise kula necklaces which return to the island in the middle of the night, hold a trading store session for fruits and vegetables on the beach and lose drastically at a game of volleyball against the villagers. The island has complicated politics. Itís difficult to tell if these are related to the kula politics. Here at Egum we really get a strong introduction to the kula business, with the beautifully carved canoes taking their proud places on the sandy beach.

Kula is a trading system begun thousands of years ago by the islanders of this part of PNG to avoid the warfare and bloodshed between clans that had become tradition in other parts of the country. Delicately carved canoes are blessed with magic before setting sail for neighbouring islands where kula transactions take place between kula partners - necklaces

called Soulava are transported clockwise around the kula ring, armbands called Mwali travel anticlockwise. Holding one of these treasured items grants status and fame to the current possessor, but the kula traders are only the guardians of these items. And there are obligations and duties that are part of the deal of being a kula player.

The kula system is still very alive here although conversations probing further

reveal that many of the magics and traditions associated with the kula exchanges

are disappearing, and quite fast. As are other aspects of the culture. There

is a tree behind the chiefís house about which all dances used to be performed ñ dances for all varieties of occasion. But the dancers now appear to paint themselves and adopt

their grass skirts when visitors like ourselves arrive.

The islandís gardens are spotless but there is an issue in waiting for rain right

now. The north west monsoon is late this year and there are concerns about fresh water supplies. Right now most of the islanders are actually drinking coconuts ñ they

havenít had rain for three months and donít see a break in the drought coming yet.

Our stay here is incredibly intense. The relationships between crew and islanders are forged very fast but penetrate very deeply. Our departure is appropriately swift ñ we stop to dive Egum Rock after we exit the atoll, to explore again the three hundred and sixty degree tour of this sea mount with bird-clad island above.

Kitava Island

January 2003

We arrive at Kitava on New Yearís Eve, in plenty of time to decorate the ship in glorious technicolour and prepare an end of the year feast. The music blasts out on

deck, alerting the entire island to our arrival, all hair is let down and the dancing rages through the night. A meteor shower around 10 pm provides grand-scale viewing. Champagne toasts at midnight to the tune of the shipís twelve bells bring in the new year and spirits soar to begin the journey in time.

We allow ourselves a day of recovery before pursuing the next tasks ñ to complete the essential meetings before Gaie and Laser leave us, to scout for a site suitable for a satellite study and to establish relationships with this culture at the heart of the Trobriand Islands.

One of the most captivating relationships developed during our time here in Kitava is with a pod of bottlenose dolphins that Michel meets within an hour of our dropping anchor. Daily trips at lunchtime encouraged the dolphins to feel safe with us, to allow us to be close to them underwater and to watch them in their playing and parading. It was very hard to leave them behind when we raised anchor almost a

month later.

Gaie and Laserís departure brings the ship to Kiriwina for a few days, the ëmainlandí of the Trobriands, where we waited for fuel for more than a week in August last year. Our

return this time is a little more productive ñ there is an opportunity to explore the island and to delve deeper into the culture, including a powerful meeting with a prominent kula trader, John Kasaipwalova. He brings to life the writings of Bronislaw Malinowski on the coral gardens of Kiriwina and takes us on a tour of his own coral gardens. His respect for the magic of the coral stone is immense.

Michele deCoust, a French writer and filmmaker also arrived while we were still in Kiriwina. She is currently working on a book of the Legends of the Heraclitus, and hoping to return to the ship next year to make a film. She had met the ship during the crazy Darwin years but had never sailed on board ñ although her own history includes three years living on a tuna boat in Australian waters.

We returned to Kitava, to the dolphins and the coral reef studies on the 15th January, struggling a little to traverse the channel between the two islands. There

is a super strong current here, up to 4 knots in places and it took some hefty motoring and zig zag course plotting to get us from A to B. This channel is ploughed daily by up to thirty major cargo ships. During our stay here, one of the islanders claimed to have even seen an aircraft carrier making its way northwards up this channel ñ perhaps an

Australian Navy vessel on its way to the gulf? These enormous ships charge up and down relentlessly and the heavy traffic is a serious source of concern for the reefs around Kitava. These reefs, especially the one we studied fringing the north side of Uratu Island, appear to have suffered a sudden catastrophe in the last couple of years. What used to be vivid hard coral gardens are now smothered in macroalgae and an incredible bloom of the Sarcophyton (mushroom leather) soft corals. But the reefs are not dead ñ all the old porites colonies, large and imposing, still stand proud and unblemished apart from fish. And there are many small new colonies taking hold again between the clumps of macroalgae.

Our science efforts are beautifully broken up by encounterswith the islanders of Kitava. A kula canoe arrives from Iwa island, this time not on kula business but to

transport a church minister, originally an Iwa man, and his wife from Kitava to Kiriwina where they will take up new missions. The canoe is beautiful, as are many of the canoes that are carefully protected around the islandís beaches. They have their own leaf houses, some even with bars, and at least one guard staying with them at all times. The kula canoes are like the Heraclitus in this respect, never left alone. This canoe, called Unfit by its witty owner, is traditionally built in four types of timber, caulked with the grated bark of they kaybass tree and adorned with a hand-stitched pandanus sail. Eibes and Michel take a trip in the canoe, watching with glee as the crew raise the sail in seconds, steer across the channel towards Kiriwina and call the wind in their melodic chant. From the Heraclitus, we watch the pandanus sail get smaller and smaller, hearing the distant call of the conch shell and wondering if these two will come back to us or have chosen to continue this voyage that could have begun thousands of years ago. Michel and

Eibes are nestled among the coconut fruits, the woven mats and baskets containing chickens and other foodstuffs. There is hardly a trace of the twenty-first century in the construction of this boat, a little plastic rope here and there, but little else.

One evening we take our fish and sweet potatoes to the beach instead of the galley to make our dinner. Each weekend there are many people here on the beach of Uratu, building fires, fishing, swimming. Without asking them, the men gather our firewood, light it, throw coral stones on top before I can blink. Michel goes into the bush to collect some leaves for wrapping the food. When the corals are black, the oven is ready. The sweet potatoes are laid down first, then the corn and bananas, then the fishes each wrapped in leaves - the whole thing covered with banana leaves and then buried in a layer of sand. The men are joking and laughing and those of the crew who have never seen a mumu before think this is all a big joke and that we will never see our food again. There is a slight edge to the laughter - like we may not eat tonight after all! These men are comedians. But after an hour of beauty, watching the full moon rise behind Kitava, the cooking is declared to be finished and the oven gently dismantled to reveal the odours of charred leaves and smouldering food, cooked to perfection.

Andrew, one of the big-men of Kitava, brings his family to the ship for dinner, along with a massive mackerel he caught earlier that day. It feeds 25 of us and there are still leftovers. Andrew has been a solid support to our stay here, entertaining us under his nut tree with stories of kula and islanders, and rallying what vegetably supplies he can from the island. Here, as in Egum, there is the beginning of a shortage of food due to the north west monsoon coming so late. But just as we complete the science study and begin to prepare for our voyage northwards, in roll the winds from the north west and they bring with them plenty of long-sought rain. We must leave straightaway, before the winds settle or become too strong ñ they will be headwinds slowing us on our 450 mile voyage to Kavieng. We must also be grateful that this monsoon comes so late this year, having allowed us to already make our way west from Honiara and north from Alotau unhindered. But the seasons have caught up with us. Anchor up, goodbye friends and dolphins, we will return in a few years.

| Jan 26 |

depart Kitava |

| Feb 1 |

arrive Kavieng, New Ireland |

(450 miles) |

Just six days at sea bring us back to Kavieng, one of our home ports in Papua New Guinea and now our departure point from Melanesia before we return in a couple of years. We

revisit our friends Sean, Shannon and Nick at Nusa Resort, Clem and Ian Tong from town and make new friends around the ping-pong table.

We had anticipated doing many tasks here in Kavieng but find the weather, the winds, a lack of organisation at the dock and a last-minute trip to Port Moresby for Eibes to get US visas for our imminent arrival in Guam all conspiring against our expected productivity. So we deal with the given circumstances and achieve what we can.

But our whole time here is overshadowed, literally, by the fishing fleet that has arrived here in search of the tuna schools of the open waters. They are armed with

helicopters and massive nets, they are blatantly bribing the local community with the by-catch that is of no value to them and they are bringing absolutely nothing to the local economy, relying entirely on mother ships that exchange fish catches for supplies. These boats are all from Asia, mostly from Korea and it was beyond the consensus of the Kavieng people to allow them into these waters ñ all deals have been made from Port Moresby. Itís a sad sight, the pristine reefs that we have experienced here in PNG ñ Milne Bay in particular ñ are under threat. This safe haven for the oceanís life is about to be exploited, leaving few corners of the world without armies of fishing boats causing more damage than just removal of the fish. Change is the only constant, this change was predictable in many ways but to see it happen before our own eyes, and in just a matter of years, is too much to take. We will now return to PNG in a few years with trepidation.

|